This continues Part 1 of a series of posts drawn from a talk I gave at O’Reilly’s online conference Experience Design for Internet of Things (IoT) on “Lessons from Architecture School for IoT Security.” You can find the slides for the original talk here. The talk encourages designers to think about security and outlines some ways UX design can support privacy in IoT applications.

When designing IoT applications for the home, we can take advantage of how much time we spend there by looking critically at the unspoken assumptions homes reveal. Living in a house is something we all unconsciously understand how to do, having learned from watching those around us before we could talk. The home is a rich environment from a cultural anthropology perspective, in part because it encodes tacit knowledge about the people who live there.

Understanding Unspoken Needs

Looking at Finland’s Hvitträsk, a home and architectural studio built in 1903 by Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren, and Eliel Saarinen, reveals extensive use of Jugendstil, or Art Nouveau, decor mimicking forms found in nature. Hvitträsk teaches the cultural context of its construction, when Finnish Nationalism was rising as Finland sought to establish a distinct identity from neighboring Sweden and from Russia, who was administering Finland at the time. Nationalism and Romanticism are values that can be decoded by looking carefully at the environment. The combination rug/blanket references coverings used for sleigh rides, and the stained glass figures reference the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic poem. These design choices reflect an emerging national identity.

Hvitträsk, built 1903, boyhood home of architect Eero Saarinen.

Hvitträsk, built 1903, boyhood home of architect Eero Saarinen.

Hvitträsk was the boyhood home of Eero Saarinen, well-known as the architect of what was then called the Trans World Airlines Flight Center, and is still in use by JetBlue passengers as T-5 of John F. Kennedy airport in New York City. Just 59 years separate the construction of Hvitträsk and the airport, but they included sweeping technical advances, from horse-drawn sleigh to commercial airplanes. One of the unspoken needs of buildings is to endure, and buildings – unlike many forms of IoT hardware – are upgradeable. Buildings are expected to last much longer than the 18-month lifespan of a device designed to become obsolete.

JFK Airport T-5, built 1962 by architect Eero Saarinen.

JFK Airport T-5, built 1962 by architect Eero Saarinen.

Security Thought-Starter

Buildings’ long lifespans challenge IoT security paradigms. There’s an inherent tension in the enduring quality of building hardware and the difficulties of keeping connected devices secure over time. Sources including the IBM Institute for Business Value caution that committing to connected building infrastructure, such as smart doorknobs with 20+ year lifespans, carries risks because a smart doorknob needs to be maintained and kept up to date against security threats unknown at the time it was built. Designers need to think critically about the path for upgrading firmware in order to reduce the risk of IoT devices becoming out of date and vulnerable to new security threats. Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems in industrial contexts have long been criticized as insecure, so designers have a chance to learn from that experience and encourage thinking about security as those systems are adapted to home use.

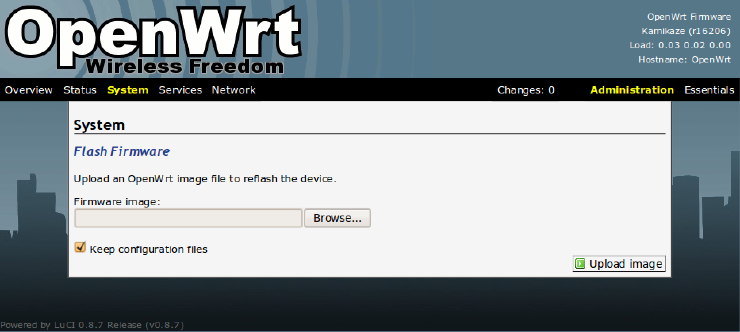

Routers are one example of a piece of infrastructure with long lifespans, still keeping the internet of ten years ago alive, often with numerous security vulnerabilities.

Detail of a router firmware update dialog box.

Detail of a router firmware update dialog box.

UX Consideration

One of the simplest ways to protect a computerized system is to install software updates that include security patches, but users often view updating software as unpleasant and disruptive. I call on designers to re-imagine software updates as a moment for positive user engagement and behavior change. Successes in chronic disease management, financial planning, and other difficult topics show that design can change behavior. Let’s translate those successes into information security.

There are formidable challenges to re-inventing something banal – people unthinkingly rush to dismiss dialog boxes unread – but new interfaces for explaining underlying security systems have the opportunity to create positive change.

This series continues with Part 3: Homes Are More than Houses

Image of Hvitträsk, by David Casteel used under CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

Image of T-5, JFK Airport, by Sean Marshall, used under CC-BY-NC 2.0

Image of OpenWRT router firmware update by Fabian Rodriguez, used under CC-BY 2.0