This fall, we had the pleasure of working with Digital Democracy on their application, Mapeo. Mapeo is a mobile and desktop app that enables indigenous communities to map their lands, sites, and resources, as well as record and monitor environmental and legal abuses by corporations and the state. The app is used by communities around the world, and due to the sensitive nature of the data being recorded, contributing to Mapeo can be high-risk for users. Our design challenge focused on user safety: how to protect end users in the likely event that a community mapper’s phone is lost, seized, damaged, or stolen.

Simply Secure uses many different Human-Centered Design methods to gather feedback from end-users, but our approach centers participants’ safety. User research with high-risk groups requires special consideration, and sometimes it isn’t always possible or appropriate to work directly with users. Here are some of the considerations we’ve encountered:

- As the pandemic continues, we face travel restrictions and closed borders that hinder global work, in addition to the risks to users and designers of meeting in-person to collaborate.

- We now lack the events, such as RightsCon or the Internet Freedom Festival, that provided opportunities for user research with people from around the world.

- American and European technologists/researchers cannot enter and do work with global communities – indigenous or otherwise – without proper attention to the colonialist dynamics that have the potential to affect the intended collaboration.

- Participating in research can be risky for the end-users because it exposes them to extra attention.

- Remote user research can be difficult in areas with network connectivity challenges and without access to certain technology.

The Mapeo project was uniquely well-positioned to overcome these challenges because Dd has a long history of local partners leading the design and development, an approach recently recognized by an M.I.T. Solver Award for Social Entrepreneurship. As Oswando Nenquimo, the Co-Founder and Director of Monitoring and Territory Defense at Alianza Ceibo explains, the Indigenous experience is central to the history of Mapeo. He says, “Together we built the open source application Mapeo for everyone to use. We were using it then, and we are still using it to defend our lands.”

In the context of our OTF Usability Lab-supported collaboration on Mapeo, time-sensitivity was front-and-center; implementing features that improve the safety of users was of utmost importance. This encouraged our process to prioritize getting a solution implemented that could be adjusted later on. We wanted to get potentially life-saving solutions integrated into the app as quickly as possible.

This led us to wonder: How do we design for quick, user-oriented solutions without conducting new user research? How do we help a team like Dd, that already practices human-centered design, lean on their own knowledge to produce user-centered solutions? Building on the collaboration with the Mapeo team, this post shares lessons to help others in similarly challenging situations arrive at human-centered solutions (especially as the pandemic continues on), but that might not have years of local information at hand. Working with Dd solidified for us that doing human-centered design is an ongoing commitment and practice, and that deep engagement and communication with your community of users, as Dd models, is the most valuable asset to doing good design work – especially in the face of challenging circumstances.

We learned four valuable lessons doing this work:

✅ Doing human-centred work is a gift that keeps on giving; start where you are, use what you have

✅ Don’t go it alone: ask your peers and community before reinventing the wheel

✅ Scenario plan: put informed empathy into action

✅ Prepare for feedback as soon as you can get it

_______________________________________________________________________________________

⚠️ Beware of a sense of techno-solutionism that can come easily when thinking through technical challenges. Threats posed to “high-risk” users or to users engaged in “high risk” activity are often socially and politically rooted, rather than strictly technical.

⚠️ Talking to users is always preferable to making assumptions. If it is safe and physically possible, do it.

1. Doing human-centered work is a gift that keeps on giving; you already have more knowledge than you realize

Even though our design team did not work directly with end-users, we had access to the Dd team, who have a wealth of user-centered information that could be relied upon to begin to answer pressing design challenges. The Dd programs team spends months on the ground with their users, and we designed activities that would help to surface their knowledge and expertise about what their users might need and what threats they face.

One of the tools we used to make the Dd team’s tacit knowledge explicit was a Threat Modeling / “Anxiety Games” Workshop. (Shout-out to our team member Cade and New Design Congress for introducing us to Anxiety Games). The Threat Modeling workshop helped to get the Dd Programs and Tech teams to talk through common threats to users, based on their knowledge of and interaction with local partners. This format was particularly relevant because, as a global organization, Dd teams operate in different contexts. People with expertise in one country were prompted to articulate some of their implicit knowledge, which created opportunities to discuss similarities and differences with other geographies.

While exploring the unique needs and challenges faced by the tech team’s defined user groups, we spent time writing down possible threat scenarios as a group. Those threats fell into four categories: Social/Political, Physical, Digital, and Environmental. We then used a game of chance to pull a selection of scenarios and talk through potential interventions.

While we led the Threat Modeling workshop before focusing our work on device seizure specifically, it a) identified device seizure as a high-priority threat to users, and b) taught us that we could rely on the knowledge of the Dd team to do user-centered work in the absence of new user research. It was a great lesson in the fact that when a team is committed to co-designing with communities and having an on-going, human-centered practice, the benefits snowball over time. Knowing your users deeply enables your team to anticipate needs and more responsibly and effectively design for them.

2. Don’t go it alone; ask your peers and community before reinventing the wheel

Mapeo and its needs presented unique challenges to a typical research and design process. For instance, front-line human rights defenders have other things to do than explain their lives to us. It was more beneficial for us to respect their time and instead work with proximate people with regional knowledge and expertise. We turned to our Slack community and other peers in the design for usable security and human rights space to learn about what design interventions have been tested and successful in similar contexts.

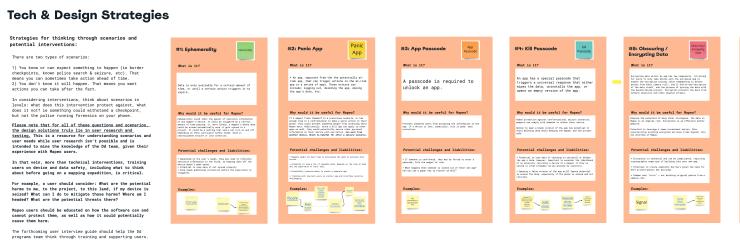

Through our own desk research and informed by Slack threads and rich conversations with some of our friends (shout-out to Carrie Winfrey from Okthanks!), We gathered a short-list of viable design options for protecting against device loss and seizure. By relying on the trusted, user-centered work of our peers, we were able to learn about how other human rights defenders have dealt with similar threats.

3. Scenario plan: put informed empathy into action

Armed with a shortlist of tested design interventions and the confidence that the Dd Programs and Tech teams had a special depth of knowledge about their users, we designed a workspace that was intended to give the team the tools to make an informed decision quickly in the absence of new data from users on the ground. As Dd is well aware, user research is critical in making key design decisions, but this strategy was our most viable alternative to arriving at an initial user-centered design decision on a tight timeline.

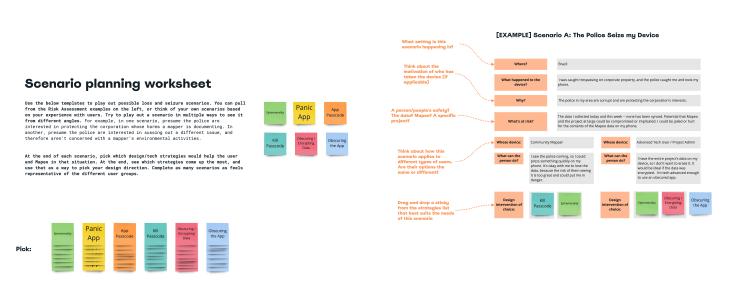

We created a large workspace in Miro that enabled the Dd team to think through the potential device seizure and loss scenarios their users face or may face and determine which of the identified design interventions made the most sense for Mapeo. The board included a synthesis of the Threat Modeling workshop findings, a section explaining each of the identified design interventions around device loss and seizure (with examples), and a section for in-depth scenario planning and pattern identification.

The scenario planning worksheet provided templates to play out possible loss and seizure scenarios. The board enabled the team to pull from examples from the Threat Modeling workshop or to think of their own scenarios based on their experience with users. We encouraged them to play out a scenario in multiple ways to see it from different angles. For example, in one scenario, we suggested to presume the police are interested in protecting the corporation whose harms a mapper is documenting. In another, presume the police are interested in sussing out a different issue, and therefore aren’t concerned with a mapper’s environmental activities. At the end of each scenario, the team was prompted to pick which of the identified design strategies would help the user and Mapeo in that situation. After playing through as many scenarios as possible, the team was encouraged to see which strategies come up the most, and use that as a way to pick their design direction for implementation.

If others are to learn from this work, we want to emphasize that it’s important to be wary of promoting any sense of techno-solutionism to these often very social and political threats. While the Dd team is conscientious of the complexity of the threats their users face, we encourage others engaged in this work to think about scenarios in levels: what does an intervention protect against, what does it not? For example, an intervention might withstand a checkpoint, but not the police running forensics on a user’s phone. In that vein, using Mapeo as an example, it is often more crucial to train users on device and data safety, including what to think about before going into a potentially risky situation, than simply updating the software’s design. How can we empower users to consider: What are the potential harms to me, to the project, to this land, if my device is seized? What can I do to mitigate those harms? Where am I headed? What are the potential threats there? As Dd well understands, Mapeo users should simultaneously be educated on how the software can and cannot protect them, as well as how it could potentially cause them harm.

4. Prepare for feedback as soon as you can get it

While this strategy works in challenging circumstances, we (and Dd) always prefer to do user research over not doing it. Therefore, we recommend proactively preparing for the availability of user input by providing a user interview guide to use once user feedback becomes possible. Ours was intended to help gather user feedback after the design strategies had been chosen and implemented and to help the team understand how the strategies were and were not serving the users’ needs.

Device loss and seizure, after all, are complicated issues with significant variations in local threats. Our hypothesis was that different geographies would have different needs. Rather than one set of recommendations for how to handle loss & seizure, the interview guide was designed for use in multiple geographies/languages/contexts to get the information needed to make more informed decisions of which tech features to implement in the future for loss and seizure, and to get a sense of whether implemented features were meeting user needs.

Working with the Dd team on Mapeo was a powerful example for us of how rigorous of a commitment true human-centered design is – and what wonderful work comes out of that commitment. We were honored to take a small part in their collaborative work that centers the indigenous communities using and designing Mapeo.

Also check out our first post on Mapeo, an interview with Digital Democracy’s Lead UX Designer, Sabella Flagg.

Credits: Katie Wilson, Ame Elliott

Illustration by: Ngọc Triệu