Last week, I encountered discussions of drones in two unimaginably different contexts: in an academic presentation at USENIX Security 2016 and on the TV comedy Portlandia. As distant genres, they offer different perspectives that have equally important UX implications for privacy preservation.

In the opening keynote of USENIX Security, Dr. Jeannette Wing examined the trustworthiness of cyber-physical systems, which are engineered systems with tight coordination between the computational and physical worlds. Some of her examples included the Nest thermostat and the Apple watch, which are very exciting user experiences to UX designers. To a designer like me, her concrete, design-based examples set an inviting tone for such a technical conference.

Drones from a technical security perspective

Dr. Wing spent time exploring points of vulnerability in which the integrity of systems, such as drones, could be compromised. This uncertainty needs management at multiple levels. For example, drones need to manage unexpected atmospheric conditions and sensor malfunctions while still operating safely. However, when flying and data collection already draw on limited battery life, there’s barely power left for anything else. Dr. Wing called for securing the full set of software running on IoT devices, from low-level device identity in hardware through secure boot and storage up to encrypted communications and secure configuration.

Slide from Jeannette Wing’s “Crashing Drones” keynote at USENIX Security 2016.

Slide from Jeannette Wing’s “Crashing Drones” keynote at USENIX Security 2016.

But preserving privacy is more than just a technical stack; the challenges that users have when operating drones contain UX lessons for privacy preservation. For that, we turn to Portlandia, which picks up where Dr. Wing dropped off.

Drones in Pop Culture

In the “Pickathon” episode of Portlandia, the two protagonists use drones to experience the Pickathon music festival virtually. By flying their drones to the front row of the concert, the two operators can see and hear everything from their couch. Although they manage to avoid long lines and smelly port-a-potties, their impact on the physical world is still felt: They injure other concert-goers—intentionally or not—as they navigate the festival.

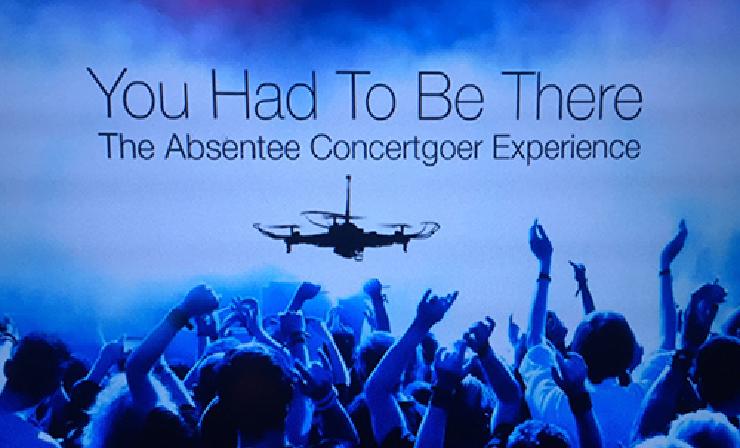

Fake advertisement in the Portlandia “Pickathon” episode for drone rentals.

Fake advertisement in the Portlandia “Pickathon” episode for drone rentals.

The plot points of the sketch unpack UX for privacy in a humorous way:

- Bystanders don’t know who’s operating them or why It’s unclear at the beginning that remote concert-goers are in control of the drones and that they have nothing to do with the official music festival.

- Bystanders don’t know what data is being collected In the sketch, concert-goers assume that the drones contain cameras but are uncertain whether audio and other data are also being captured.

- Subjects under observation are unsure of how to interact with remote operators The operators can broadcast their voices through the drones, and one annoyed concert-goer was surprised to discover that “this thing can talk.” The operator taunted the concert-goer into a fist fight in which the concert-goer curses the absent operator all the while getting beat up by the drone.

- Bystanders and subjects don’t know where the drone operator is located When the freshly bruised concert-goer breaks open the drone, he sees a label with the operators’ address. He shows up at their house to beat up the operator who goaded him during the fight.

- When operating a third-party drone, an external carrier might be able to both monitor and override control of the drone from afar At the end of the episode, the bruised concert-goer makes peace with the operators and joins them on their couch. While all three enjoy the concert via drone operation, the entrepreneur who rented the drone to the operators appears in the background. In his quest to make music festivals appealing to music fans over age 40, he had snuck into their home to watch them and gather data points.

The concert-goer who was cut up by the operator’s drone in Portlandia’s “Pickathon” episode.

The concert-goer who was cut up by the operator’s drone in Portlandia’s “Pickathon” episode.

How drones challenge us to design for privacy

Drones are a useful example when considering privacy because they make every actor in the system visible. In contrast to contexts such as mobile messaging on a phone, drones are less abstract because you can see the operator, owner, and subjects under observation.

Here are two key UX design challenges for people working on IoT applications more broadly:

- How can embedded sensors disclose the data they are collecting, who is collecting it, and for what purposes? Without a service design component, policies such as a hypothetical drone registration service won’t help people understand the who, what, where, and why behind the drone’s operation. As an analogy, many commercial trust don’t just have a license plate to identify them. They also display decals that ask, “How’s my driving? Call 1-800-XXX-XXXX for complaints about vehicle number N.” Because of the decal, other drivers now know of another channel to learn more and hold truck drivers accountable. Nothing similar exists for drones.

- What best practices for zero-UI or design-beyond-the-screen can be used to help bystanders interact with drones? Dismantling a drone to find a physical street address like in Portlandia may be comedic, but it is neither common nor scalable. With weight and power at a premium on drones, there is no space to add instructions on how bystanders should interact with the drone. One solution is to use bystanders’ cell phones displays, but that approach is also problematic. It is highly unlikely that we can scale the use of mobile notifications to inform bystanders of their rights and the drones’ purpose. Even if notifications were mandatory, the thousands of IoT devices alerting bystanders through their smartphones would be an unnavigable user experience. We need to explore these issues more deeply.

Drones lead the way

Drones are complex cyber-physical systems with poor ability to disclose how they work to bystanders. In contrast to the relatively well-understood domains of email and mobile messaging, privacy-preserving measures for drones are significantly more complicated. Because the challenges for drones are new to both the public and the technical community, they provide an opportunity to engage a mass audience in critical thinking about how we want to interact with the systems.

Through drones, designers can explore particular challenges such as alert management. By thinking about how multiple parties (owner, operator, subjects under observation, privacy advocates, etc.) want to interact with drones, thoughtful UX design can empower people to manage their privacy in a variety of contexts.