The Project

OCCRP, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, is a nonprofit that enables “follow the money” journalism all over the world. They’re an invaluable resource for training and supporting journalists who do the dangerous, unpopular work of bringing the shadowy side of international finance to light.

One tool that OCCRP maintains is Aleph. Aleph is an open-source portal for exploring datasets related to journalistic investigations into businesses, especially corruption, money laundering, and organized crime. It’s a key tool for many journalists, both freelance and newsroom, working on these and related issues.

The team that maintains Aleph approached us looking for help with the user experience design of the data portal. They knew it was difficult to use, and they knew that some fundamental aspects of the information architecture and UI needed clarifying, but they weren’t yet sure what or how, making this challenge a perfect fit for our human-centered design approach. We rolled up our sleeves and jumped in.

The Process

The research phase started with 5 exploratory interviews with journalists to identify pain points and opportunity areas within OCCRP Aleph. We spoke with 4 freelance journalists and 1 newsroom journalist, and the interviews were a mixture of in-person and remote. We identified three problem areas that kept emerging, and pulled out details and quotations in order to clarify these issues and bring them to life.

After our interviews were finished, we shared our findings with the OCCRP team and worked together to decide how to prioritize our design time.

We decided to focus on the following three themes in our design work:

- Purpose, e.g. What is this tool for? Who makes it? What kind of data does it contain? How is it different than other tools?

- Orientation, e.g. Where am I in the database? How did I get here? How do I get somewhere else?

- Sourcing, e.g. Where is this data from? How fresh is it? Is it publicly available or private? Who vouches for it? Can I consider it a credible source?

With these focus areas, we iterated on wireframes and high-fidelty prototypes for the Aleph interface, and then ran 4 remote usability tests with OCCRP journalists to get feedback on how the wireframes addressed these themes and see if our designs improved their workflows.

Our collaboration formally ended in August 2019, when we handed off our research, our mockups, and our usability test results to the Aleph team. Since then, the Aleph team has been hard at work making these research-based design recommendations into reality. The screenshots you see below aren’t just pipe-dream design mockups – they’re images of the actual website.

You can explore these changes for yourself at http://aleph.occrp.org. (Not sure if this is a benefit or a hazard, but you’ll likely learn a bit about the shadowy world of international corporate finance along the way.)

Unpacking The Design Problems

In this case study, we’ll walk you through some of the design problems we identified in Aleph, as well as how we solved them. You may recognize some of these design problems in your tools and teams, and we hope that our process and solutions are helpful to you.

Problem 1: What is this tool called?

In our post-research meeting with the OCCRP team, we decided to redesign the home page in order to make people’s first steps clearer. But we ran into an unexpectedly thorny problem: what name should show up on the home page?

Obviously, the name of the tool. Easy, right? Well, even in the corporate world, but especially in the nonprofit tech and open source world, it’s not so simple.

What we did to solve this problem is listen carefully to how our interviewees referred to… well, to the tool. As interviewers, we went to great pains not to put any words in their mouths. We heard the following names:

- “data dot occrp dot org”

- “OCCRP Data”

- “OCCRP”

- “Aleph”

- “OCCRP Aleph”

In reflecting on this challenge with the team, we dug into the name tension and found that the OCCRP team really liked the name that had been reserved to just refer to the code base: Aleph. The name Aleph is actually a literary allusion. The Aleph is a magical object in a Jorge Luis Borges story; discovered under a staircase in an old house, this glowing sphere contains the entirety of the universe, past, present, and future. Aleph, the open source project, also aims to contain a dazzling, head-spinning variety of information.

OCCRP Aleph is a tool that allows journalists to upload, search, and cross-reference large data sets, often around business structures and property ownership. Datasets like these are crucial to “follow the money” investigations such as the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers.

So why not just call it Aleph? Since Aleph is open-source, anyone can run an instance of it on their own web servers. Newsrooms, such as the Süddeutsche Zeitung, have their own private Alephs.

Out of these names, we determined that the name OCCRP Aleph should show up on the home page, while the project should still be called Aleph. We all loved the name, and even had some fun with a new logo… but more on that later.

Problem 2: Orientation — What goes on the home page?

If you visit an Aleph installation to look at datasets, you have two ways of encountering the datasets. Either you can search datasets for certain people or companies, or you can just browse entire datasets and see what you find. But do people actually do both of these things? We learned in our research phase that people use OCCRP Aleph almost exclusively to search. They come to OCCRP Aleph once they already have a lead they want to follow up on, the name of a person or a business. Nobody browses. Nobody starts out by “exploring.” OCCRP Aleph is rarely the first step in their research process – it’s always the second.

But if people already know what they want to search for, and they aren’t interested in seeing anything they weren’t looking for, then what shows up on the home page?

You’re familiar with the ways that, for example, an e-commerce website solves this problem. An e-commerce website uses the home page to spotlight sales and deals; they recognize you from your past behavior, and push products to you that they think you’ll click on. However, neither of those techniques makes any sense for an open data platform that doesn’t track visitors. We had a few different patterns we could try.

Should we just emulate the classic, minimalist Google homepage, with a single search box? Or should we make the home page a personalized area, a shortcut to a user’s private groups and uploaded datasets? Or something in between?

Most Aleph users are repeat users, so personalization seemed like a good idea. However, usability testing surfaced a few problems that needed to be addressed.

People found it confusing when the first screen they saw was too customized. They also pointed out that, if personal search history, datasets, and other groups were shown immediately on the front page, somebody looking over their shoulder when they logged in might see sensitive information. So we had to make sure that what they saw was personal, but not too personal. We settled on a list of events: data added or removed from datasets they follow.

This design acknowledges that search is users’ main task. They come to OCCRP Aleph with a list of names, a list of organizations, or at the very least a question to look into. So we added heavy visual emphasis to the search box at the top of the page.

We also made a subtle improvement to help people orient themselves: we added a dropdown menu in front of the search box. The dropdown shows the scope of the current search – the dataset(s) to which the search is being applied. When it says “OCCRP Aleph,” that means all datasets available to that user.

On the datasets page, the dropdown isn’t a dropdown yet, just looks like a label.

However, once you enter a database, the label becomes a dropdown. You can choose whether to search within the database you’ve selected (here, “Mozambique Persons of Interest”) or whether to search the entirety of the Aleph instance. This dropdown offers more than just a choice: it sends a quiet signal to help you build your mental map of where you are.

This new design gets people right down to business from the beginning, and, as an added benefit, cuts down on that “where am I and how did I get here?” feeling.

Problem 3: Sourcing — The heavy burden of verification

“How reliable is this data?” This is the crucial question journalists ask whenever they are researching a story. Using outdated, falsified, hacked, or even incomplete data can cause serious consequences.

Aleph is in a difficult position here. OCCRP can’t vouch for each and every data set. OCCRP provides software that helps journalists search datasets and trace connections between datasets, but OCCRP can’t curate every dataset on OCCRP Aleph, much less every dataset on every Aleph installation!

In our research, people expressed a lot of concern about data reliability. They asked for a lot of features that frankly aren’t possible: “trust scores,” verification marks, and automatic updating of datasets. But Aleph isn’t supposed to be a data evaluation tool. No software can substitute for the judgment of a trained journalist who is familiar with their subject area.

Just to give one example: a three-month-old dataset with company addresses might seem recent enough to use… but not for a seasoned business journalist, who already knows that this dataset is updated monthly!

This is why our philosophy was Data transparency, not data perfection. We aimed to spotlight all metadata that could help a trained journalist evaluate a source’s recency and provenance. Most of these fields already existed in the data model – it would have been difficult to add new fields – but we used design to draw attention to the most relevant ones. In particular, we recommended a bold callout that shows the dataset’s update frequency, if known – and if it’s not known, that’s also helpful information.

Inside the dataset, people can see even more metadata. It’s spotlighted with a darker box. This information may not reassure journalists that this dataset is clean, uncompromised, and updated, but it gives them the information they need at a glance in order to make the necessary judgment calls.

Little Design Changes, Big Impact

Our research and usability testing helped us uncover lots of design opportunities along the way that weren’t quite as game-changing as the ones above, but nevertheless led to significant usability improvements. Let’s look at a few places where the OCCRP team added a little intervention that makes a big difference.

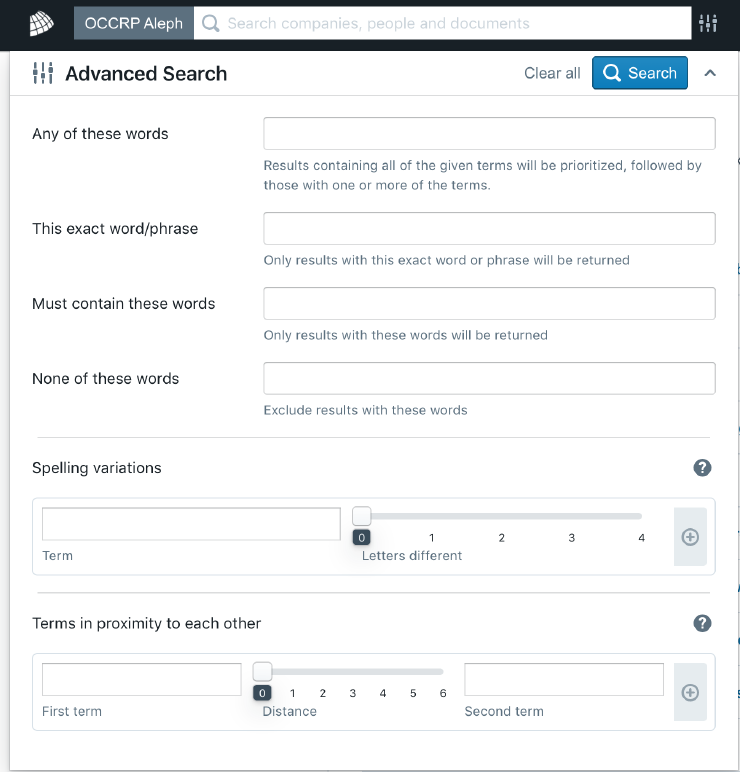

Search tips. Even people who used Aleph often had a hit-and-miss approach to advanced search. Since they use a lot of databases, all of which behave a little differently, they don’t remember exactly which conventions Aleph uses. To solve this, we built a giant dropdown advanced search panel that is packed with explicit reminders about how search works. It’s always available, right next to the search bar.

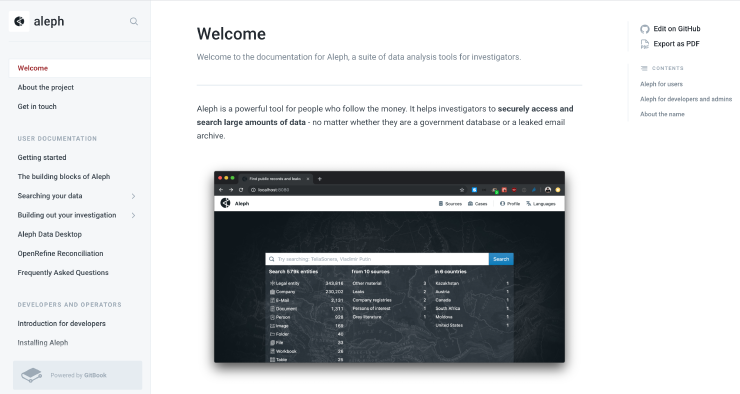

Documentation for non-developers. Previously, it was much easier to find information about how to contribute code to Aleph than how to use Aleph. Figuring out how to do journalist tasks like searching, parsing, uploading, and sharing datasets was a challenge, since the documentation was geared towards software developers. The new documentation page, located at docs.alephdata.org, is written for researchers and journalists, and built around the tasks they’re likely to do.

Quick links to user settings. Accessing various personal settings used to mean first going to a personal home page, then navigating to the place you wanted to be. We designed a menu and architecture that made navigation more efficient by surfacing common user tasks in a dropdown.

And finally… We say over and over, “design is more than logos.” But, yeah… we did design a new logo for Aleph!

This simple shape, inspired by the ancient Phoenician glyph for the letter “aleph,” is a high-contrast emblem that looks great in many different colorways. We work as a team and usually don’t emphasize the contributions of individuals, but in this case we have to shout out to Lorraine Chuen for her modern take on the ancient symbol.

We hope learning about our approach was useful to you. Would you like to collaborate with us to solve similar design and usability problems? Get in touch!

Thanks to Emma Prest, Kirk Jackson, Friedrich Lindenberg, Nadine Stammen, Lorraine Chuen, and all research participants.