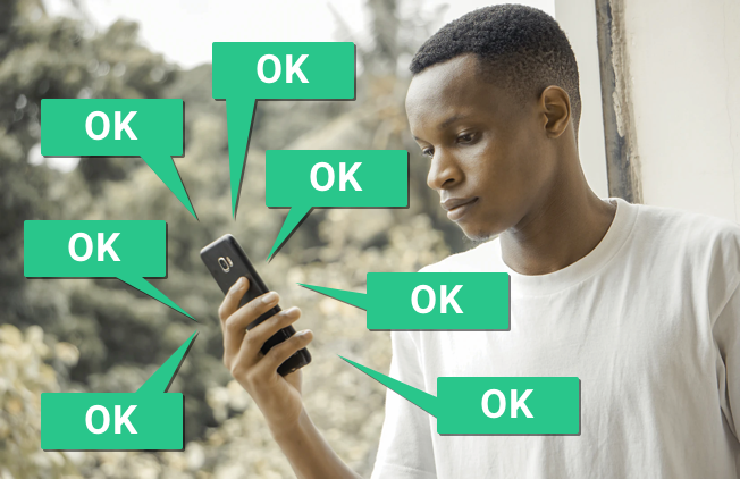

When was the last time you actually read one of these alerts? Have you ever clicked through to read the full policy? Have you tried to make changes, or say “no” to the trackers? I know I sometimes don’t – too often, I find myself just looking for the “Accept” button.

If you are in Europe, you probably see an alert like this every time you load a new webpage or install a new app. These are the result of increased regulation in Europe around privacy (read more about the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR). This legislation requires that companies get your explicit consent before they use your personal data. “Personal data” isn’t just your demographic, health or banking data — it’s also the behavioral tracks you leave behind every time you use digital devices, like your browsing behavior, the type of device you’re using, the language you view content in, where you’re connected from, and more.

Getting our consent every time companies use this data sounds like a great idea. So what’s the catch?

Unfortunately, the way that companies are actually implementing this consent process is often less about making sure you understand what’s going on, and more about satisfying the law’s bare minimum requirements. Much of the “consent” that you’re likely to give online doesn’t even meet the GDPR’s standards. Overwhelming you with legalese, or manipulating you with misleading design, is a strategy to get you to click “accept” – designers often call this a “dark pattern.” But this tactic is actually illegal in the EU – the GDPR requires that consent be “informed” and “explicit.”

There’s a deeper issue too, though: even if every company did design a perfectly informed, explicit consent process, we’re still relying on every individual to make decisions where they can’t know the future and don’t have all the information. Does my clicking “accept” in the moment mean that I am okay with my data being used forever? What if my identity is stolen in the future? What if I’m a target of harassment? What recourse do I have, if I already said “yes” to sharing my data? As Julia Powles writes in the New Yorker: “the actions of any one person are unlikely to effect change, and so it is comparatively easy for us, as a collective, to yield certain concessions out of convenience, ignorance, or resignation.”

So what if, instead of asking how we can improve these alerts, we stepped back and asked questions like:

- How might we consent to sharing our private data in a meaningful and engaged way?

- How might we build technology and systems where less private data is needed to begin with?

- How might we design a better digital world where technology protects us while helping us achieve our goals?

These questions have been on my mind a lot lately. They were a major topic of the discussions I had recently as a guest on the Wireframe podcast (by Adobe/Gimlet), and also in my talk at the MyData conference in Helsinki. As practitioners in field known for innovation, we aren’t approaching this problem like a design challenge. And as people using these technologies, we need to stand up and demand better. Given the daily deluge of data breach notices, all of us — companies, end users, governments — should have similar interests here. Our data is becoming more and more valuable, so the risk of breaches is getting higher and higher. Why not rethink and redesign the whole system with privacy, not just consent, in mind?

One way that we’ve approached this at Simply Secure is by incorporating techniques like threat modeling which we’ve learned from the information security communities into our design practice — making privacy, security and safety central to design. By thinking through risks and threats, and when possible working with and co-designing with people from at-risk or vulnerable communities, we can work together to design for not just normal-use best cases but also stressful, higher-risk scenarios. By bringing more diverse perspectives to the design process and incorporating real world experience and user feedback, we have the opportunity to design responsible interfaces that take into account not just user needs but user safety and privacy.

Redesigning the tools, systems, and norms we’ve grown accustomed to is an uphill battle, but there truly is hope and potential for better more responsible technology.