Most people who spend time online have a general idea of what “phishing” is, but it can be hard for folks outside of the security community to pin down an exact definition. Understanding the threat that phishing attacks pose can help designers and other UX experts become effective advocates for experiences that protect users. In this post, we will explore the basics of how phishing attacks work, and in a follow-up post, we will examine some of the mechanisms that protect users against them.

Phishing is social engineering

As of this writing, Wikipedia defines phishing as “the attempt to obtain sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details (and sometimes, indirectly, money), often for malicious reasons, by masquerading as a trustworthy entity in an electronic communication.”

- A definition of the term “phishing,” adapted from Wikipedia.

What does this really mean? Implicit in this definition is the idea that phishing attacks target people; they are an example of what security experts call a social engineering attack. This is in contrast to many of the other digital threats we hear about, such as exploits that take advantage of flaws in particular software programs (e.g.: buffer overflows, SQL injection points, or cross-site scripting opportunities) or assaults that take aim at the limitations of a computer system (e.g.: denial-of-service attacks).

Social engineering attacks are just a modern take on the classic confidence trick, which derives its name from the attacker’s methodology of building false confidence – or trust – with the target before attempting to defraud them.

- A definition of the term “confidence trick,” adapted from Wikipedia.

Other examples of social-engineering attacks include advance-fee scams (beware of people claiming to be Nigerian royalty!) and the elaborate scheme that Mary McDonnell’s character uses to steal a key card, thus allowing Robert Redford’s character to access a locked building in the movie Sneakers.

A sample attack

Again, the aim of a phishing attack is to harvest confidential information from users. Let’s walk through a hypothetical example to see what this looks like in practice.

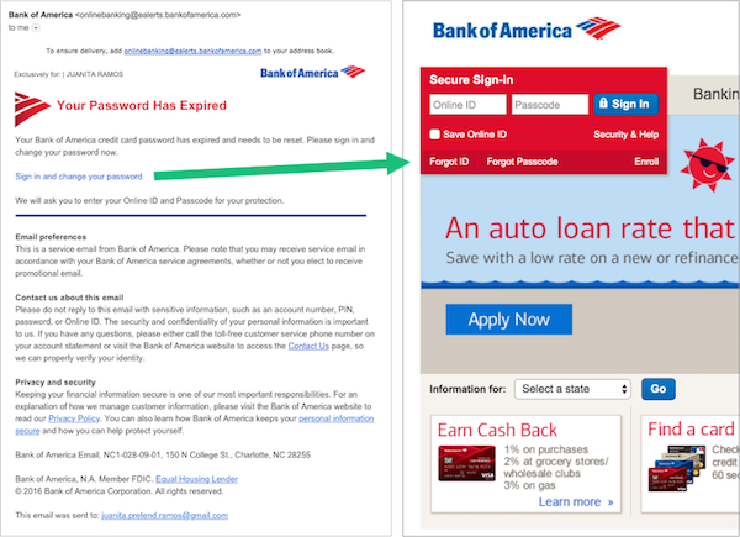

- Juanita gets an email that looks like it’s from Bank of America, saying her password needs to be reset, and it offers a link that allows her to take this action.

- Juanita clicks on the link and sees a webpage that looks similar to the one she is used to using.

- She enters in her username and her password.

- The page returns an error, saying that the password she entered is incorrect. Like many people, Juanita has a small number of passwords that she reuses across many sites. She tries a few different passwords, trying to find one that works.

- Juanita eventually gives up, clicks the “Forgot Passcode” link, and sees that the site returns an error message asking her to sign in again later.

At this point, the attackers have probably gotten:

- Juanita’s bank username

- Juanita’s bank password

- The passwords of several other services Juanita uses, potentially including the one she uses on her email account

They accomplished this because:

- They sent a message pretending to be from Bank of America to an actual Bank of America customer.

- They spoofed the “from” address in the email, so it looked like it was really coming from Juanita’s bank.

- They created an email that looked and felt similar to the emails Juanita regularly gets from her bank.

- They created a webpage that looked and felt similar to the one she’s accustomed to.

- They took advantage of Juanita’s uncomfortable relationship with passwords; she wasn’t sure that she was typing the right one, so inadvertently shared several others as well.

- A mocked-up phishing email and sign-in page.

The practical threats of phishing

For their attacks to be successful, phishers must create an environment where people feel comfortable sharing confidential details. Attackers harvesting credit card numbers might create a fake version of a popular online retailer or a government website to collect social security numbers.

Email credentials – the username and password you enter when you sign in to your email account – are a particularly juicy target because most sites use email as a password-reset mechanism (for example, when you click the “Forgot your password?” link on Amazon.com’s sign-in page, they send a code to your email account as the first step in resetting your password). Thus, attacks against your email account are about more than getting access to your email messages; they’re about using your email account as a jumping-off point to get access to the rest of your digital life, too. There are also other ways in which a phishing attack may be just the first of a multi-step attack; if you reuse passwords, one successful phish can end up compromising many accounts.

Similarly, if you reuse passwords from one account to another, a successful phishing attack against one account can easily end up escalating into something more serious. Where possible, try to use unique passwords for your high-value accounts and consider using a reputable password manager that isn’t based in the cloud, like 1Password (stay tuned for my next post on phishing, where I will explore this and other defensive mechanisms in more detail).

Advanced attacks

Early phishers focused on compromising a large number of random accounts, but their attacks quickly evolved to become more targeted. Rather than send emails to a million hotmail.com accounts, attackers will sometimes do meticulous research and craft a message specifically designed to appeal to the staff of a particular organization. This message might be designed to look like the sign-in page for the organization’s internal web portal or for its health insurance provider. If the attacker is an employee or knows someone who works at the organization, they may reference information that only insiders would know.

For example, imagine that Hamidou works for Collective Insurance of Brooklyn, a large company that conducts much of its business online. He recently started working there and is still learning how to navigate the company’s employee benefits website, which he thinks looks very outdated. This benefits site is managed by a firm called BenefitsDigital, which specializes in benefits management but hasn’t updated the styling on their site for a long time. While accessing it during new-employee orientation, Hamidou noticed that it has a strange URL like collectiveinsurancebrooklyn.benefitsdigital.com. his HR representative explained that this is to be expected because the site is hosted by the benefits administration company.

An attacker saw Collective Insurance of Brooklyn listed on BenefitsDigital’s “Our Clients” page, and used a LinkedIn search to discover that Hamidou and a few other people started working there recently. Further sleuthing revealed that most employees at the company have email addresses of the form firstname.lastname@. From there, it was easy for the attackers to send this small group of employees a customized message that looked like it came from BenefitsDigital. The message tells them that they need to sign in to the website and perform their quarterly benefits review to prevent a discontinuation of their 401(k) matching, and helpfully reminds them that they are eligible for a $200/month commuting reimbursement.

Hamidou clicks on the link in the email, which brings him to collectiveinsurancebrooklyn.ebenefitsdigital.com. His eyes skim over the long URL and he doesn’t notice that the site is hosted at ebenefitsdigital.com (a site the attackers set up to mimic the legitimate benefits administrator), not benefitsdigital.com. The website is just as weirdly outdated and buggy as ever, so nothing seems out of place to Hamidou. When he tries to sign in, he gets an error message that the site is down for maintenance. He decides he will try again a few days later.

- A definition of the term “spear phishing.”

Attacks similar to this example is not just believable, but becoming increasingly common. As you might imagine, a customized message that references an organization’s cultural touchstones is less likely to set off alarm bells for its victims and has a higher probability of success. If the phisher’s goal is to gain access to the organization’s internal systems, a customized attack can can be successful if just a single employee bites.

Even more sophisticated attacks combine inside knowledge with a sense of social pressure by making the emails personalized to individual targets, and making it seem like the message is coming from a senior member of the organization, such as its CEO (apparently, this kind of attack is now called “whaling”). If you’re a lowly payroll processor and you get an urgent email from someone six levels above you in the corporate hierarchy – on the day where the rest of the department is at a retreat! – it can be hard to keep your cool and tune in to the possibility that the inquiry may not be legitimate. And, even if you do get a sense that the request may not be legitimate, how do you verify your hunch without simultaneously insulting a bigwig and torpedoing your career?

Phishing is about confidence

As I remarked before, phishing is just one modern take on the idea of a confidence game. A successful attack depends on the user developing confidence that the request for their information is legitimate. Social pressures, such as in the whaling example, can make it hard for users to see an attack for what it is. So can general discomfort with computers or a lack of experience dealing with sensitive information.

- The 2002 movie Catch Me If You Can publicized Frank Abagnale Jr.’s adventures as a young confidence trickster. Frank (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) is the epitome of the term “confidence man,” or “con man” for short.

It’s important to note that falling for a phishing attack does not indicate any kind of failing in a person’s intelligence. The skills we’ve evolved over millennia for developing trust in other human beings – evaluating appearance, behavior, and pattern-matching – do not serve us well in a digital context. The channels we have for receiving trust information from computers, such as the visual design of a website or the “from” header of an email, are simply too easily spoofed. When push comes to shove, if you create a website that is a faithful replica of bankofamerica.com, you will find people who will trust it based on its visual design alone.

In a future post, I will review some of the mechanisms that exist to help users and organizations protect against phishing attacks and explore ways that designers can contribute safeguards through their products. In the meantime, do you have a favorite story about phishing or other forms of social engineering? Connect with us on Twitter and tell us all about it!